Amelia Peláez y de Casal was born in the second year of Cuba’s final liberation war against Spain on January 5th, 1896 in Yaguajay, the province of Las Villas, Cuba. Her family was part of the Cuban-Creole middle class, and was well-off both economically and socially as her father was the County Doctor Manuel Peláez y Laredo. In addition, her mother Maria del Carmen del Casal y Lastra was the sister of the great Hispano-American modernist poet Julian del Casal. This association brought Peláez’s family into the highest intellectual circles of Cuba.

Peláez was born to a family of many children, and they all began their schooling under Sra. Carmen del Casal y Lastra who had attended the Covenant and Academy of Visitation in Mobile, Alabama. Because of Cuba’s position under Spain, education was dominated by Spanish Roman Catholic elite. Homeschooling in the case of the Peláez children likely gave them a less bias education and allowed their mother to teach them as she wished, not under a Spanish curriculum. Peláez’s first education in the world of art was under a painter named Doña Magdalena, who had previously been an activist in the independence movement that coincided with the war from 1895 to 1898.

In 1915 Doctor Manuel Peláez y Laredo became sick and relocated his family to Havana where they could live in more comfort. Although he died within the year, the house within which he had established his family would last them a lifetime. Number 261 on the street Estrada Palma in the neighborhood of La Vibora came to be both the dwelling of and inspiration for Peláez in her later years. The house, called Villa Carmela after Peláez’s mother, was built in 1912 and incorporated aspects of both neoclassical design and more traditional Cuban Creole architecture. The towering white facade and columns brought in neoclassical design elements, and columns such as these can be seen in the background of numerous Peláez paintings. Creole architecture brought in more decorative elements, and the wrought iron fence as well as ornate windows are the best examples of this in La Villa Carmela. In the backyard a pavilion surrounded by plants and birds would become Peláez’s primary workshop, and this natural insparation would come through in some of her paintings as well. Pieces of Peláez’s art would line the walls and the hallways in La Villa Carmela, filling the house with paintings that it helped to inspire (Gómez-Sicre 12).

In 1916 Peláez began to study painting at the San Alejandro School of Fine Arts, where many members Cuban painters in her time began their studies. The majority of the artists teaching there practiced the French neoclassical styles that drew inspiration from similar Greek and Roman styles. These practices did not speak to Peláez and her own feelings about art, but she managed to find a cultural and artistic mentor in a 1918 color class with teacher Leopoldo Romañach (Gómez-Sicre 13). Romañach, although he practiced romantic realism, was tolerant and accepting of many more forms of artistic expression. His influence on the art of Peláez can be seen in her painting Veleros from 1925, which has a maritime subject similar to all work by Romañach and uses his palette and soft brushwork (Gaztambide 86). In 1924 Peláez spent her break studying at the Arts Students League in New York under Professor Bridgman (Gómez-Sicre 13) which was a trip unique to her education, but that trip also left her largely unsatisfied with the limited styles of art that she had been exposed to. Taking matters into her own hands, she traveled to Paris in 1927 with a scholarship from her Alma Mater as many of her peers were doing.

Accompanied by fellow aspiring artist Lydia Cabrera, Peláez took classes all over the city at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, École des Beaux-Arts, and the École du Louvre. After four years of studying French artistic styles Peláez had still not found her niche in painting and enrolled in Fernand Léger’s Académie Moderne. Here she studied scene design and color dynamics under Alexandra Exter (Gómez-Sicre 14), a woman who had a huge impact on the art and life of Peláez. Exter introduced Peláez to modernism (Blanc 14), abstraction, and new and unique ways to express forms and use color. Peláez also learned from Exter a sense of self and determination as a professional female artist (Gaztambide 86).

In 1933, Peláez showed 33 works at the Galerie Zak, located on the Rue de l’Abbaye in Paris. Her collection there consisted of 21 still life paintings, nine landscapes, and eight portraits of women. The exhibition was very well received (Gómez-Sicre 14), and the year later she returned to Cuba in the wake of that success.

38 years old and back in Cuba, Peláez found herself in the middle of a country in economic and political frenzy. Her first solo exhibition back home was at the Lyceum in 1935, a women’s organization with the goal of promoting Cuban culture through art, music, and literature. Additionally, upon Peláez’s return she became a member of the Cuban avant-garde movement, the vanguardia.

One of the sources of the political activity in Cuba was the cry for autonomy and hope for a new governing system. The vanguardia helped to promote nationalism in this time (Gaztambide 88) by using art to explore and define Cuban culture as its own entity. While other artists explored afrocubanismo and criollismo, which studied afro-cuban and euro-cuban descent respectively, Peláez focused on her experience with cubanidad (Gaztambide 88)which explored the roles of the secluded and often controlled upper class women, as her family roots in native Cuban culture allowed her to do (Luís sect. 3: Amelia Peláez).

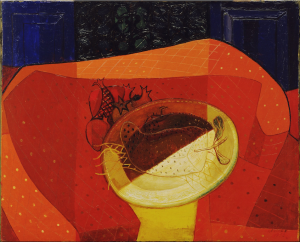

Her paintings grew to have a more feminine and feminist focus (Blanc 14) as Peláez returned home to Cuba. Her work completed at home is a demonstration of the development of her signature style with inspiration from fruit, architecture, and traditional Cuban stained glass (Luís sect. 3: Amelia Peláez). Two examples of her works that show feminine themes are Marapacífico (1936) and Naturaleza muerta en rojo (1938). Marapacífico represents many of the lessons that Peláez learned from Exter (Blanc 14), and shows the hibiscus, which is a very feminine and sexual flower especially in red, and is accented by curved lines that imply abundance. These thick lines that organize the painting are representative of Exter’s work. Naturaleza muerta en rojo also plays with fruits such as the

guanabana and the pomegranate to convey a sense of fertility. In the background of this painting there is also play with thick black lines, which evolves in later paintings to show Cuban colonial architecture (Pau-Llosa 7-8). Siesta (1941) expands on the architectural elements that she hinted at in previous works, and this expression of architecture only became more pronounced through the 40s (Martínez 128).

While her artistic style was developing, Peláez also spent periods of time working exclusively in one medium. She worked almost exclusively in pencil between 1935 and 36, taking small detours to construct two fresco murals (Gómez-Sicre 15). Another one of these periods occurred in the early 1950s, when she focused on pottery and constructed the ceramic mural for the National Accounting Office (Gómez-Sicre 12,16).

Although paintings by Peláez can now be sold for thousands of dollars, it was extremely hard for her to make a living as an artist. Her first exhibition in Cuba after returning from Paris sold no paintings, and she spent a lot of time teaching art locally to supplement her occasional income from sold works (Martínez 28-29). Another difficulty she faced was the acceptance of modern art. It was a growing practice but many people did not accept the stylistic approach. The 1940s finally put Cuban modernists on the map with a traveling Modern Cuban Art exhibition that visited the U.S, Europe, and Latin America (Martínez 26). In 1941 Peláez’s work was shown for the first time in New York for the magazine Norte, and this led to multiple purchases of her art by the Museum of Modern Art in the following years (Gómez-Sicre 16).

Her perspective as a woman gave Peláez a special place in the world of the vanguardia because she was able to look at Cuban life and tradition from a different perspective. She existed much more privately than her fellow vanguardia painters, and was only one of a few women to participate in the movement of Latin American art (Pau-Llosa 7-8). Peláez’s perspective on cubanismo contributed in special ways to the realization of Cuban tradition, and her unique visual language conveyed her social concerns and emotions to her audience.